Prerequisite: Planning 2 or dean's permission

Units: 3.0

Classroom: online via Microsoft Teams

Class Time: Thursday: 9:30 AM-12:30 PM

Office Hour: Thursday: 12:30 PM -12:45 PM - Right after class time

Instructor: Zhuo Yao, Ph.D.

Instructor: Archt. Carmela C. Quizana

Thursday, December 15 2022

Instructor:Zhuo Yao Ph.D.

Instructor: Archt. Carmela C. Quizana

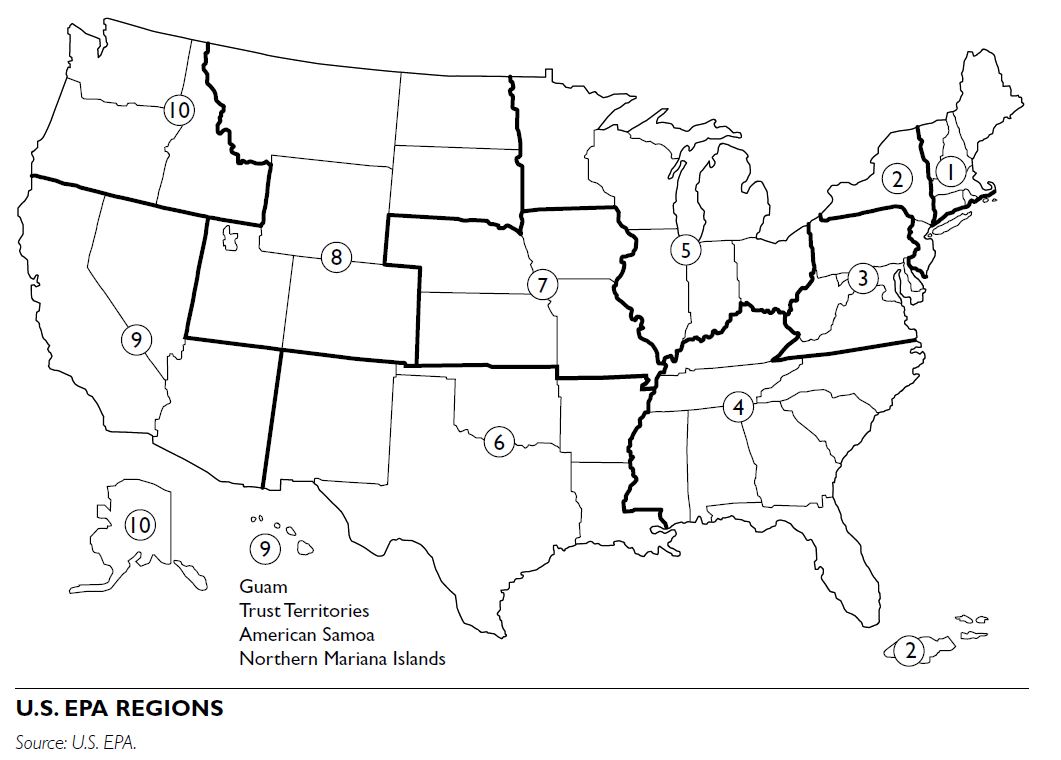

REGIONS

Regions are areas that have a characteristic or group of characteristics that distinguish them from other areas. These characteristics can be defined in terms of political, physical, biological, social, economic, cultural, or other factors. The structural and functional organization of these factors varies from place to place.

Governmental agencies and others use the term “region” to delineate multijurisdictional areas, such as those composed of more than one town, city, county, state, or nation. Environmental scientists identify regions in reference to parts of the surface of Earth, such as drainage basins, physiographic provinces, climatic zones, or faunal areas. Geographers define a region as an uninterrupted area possessing some kind of homogeneity in its core, but without clearly defined limits. It is important to understand that different types of regions exist, and that the idea of regions presents an important concept for planning and urban design.

For planning and urban design purposes, regions may be defined by political, biophysical, ecological, sociocultural, or economic boundaries. One particular type of region, the metropolitan region, often covers several of these types, because they can serve several purposes. The discussion here focuses on state-level regions and then addresses metropolitan regions.

Maps representing regional boundaries differ among various academic disciplines and government agencies. Because of these variations, the information provided here is not an exhaustive listing of all the types of regions that impact planning; rather, it is provided as a starting point for identifying various regions and regional influences that play a role in planning and urban design.

Political Regions

Political regions are civil divisions of areas. They may be defined at scales that are easily recognized, such as state, county, and township boundaries. These types of regions, known also as governmental jurisdictions, define areas that possess certain legislative and regulatory functions, important to planners and designers.

Political regions may also be groupings of areas, such as multistate regions, that are defined by political entities to serve certain regulatory, policy, and information delivery purposes from the federal level.

Biophysical Regions

Biophysical regions may be described as the pattern of interacting biological and physical phenomena present in a given area.

Perhaps the most commonly identified type of biophysical region used in planning is the watershed. For example, since the 1930s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has used watersheds for conservation and flood-control planning. Likewise, the U.S. EPA promotes watersheds for regional planning and maintains a “Surf Your Watershed” website (www.epa.gov/surf). Watersheds are important to define for numerous purposes, such as protecting drinking water supplies and identifying wetlands mitigation sites.

Purely physical and more complex ecological regions can be mapped. For example, watersheds are mapped by following drainage patterns, which are relatively easy to trace on a topographic map. Physiographic regions are based on terrain texture, rock type, and geologic structure and history.

Ecological Regions

Ecological regions are delineated through the mapping of physical information, such as elevation, slope aspect, and climate, plus the distribution of plant and animal species. The U.S. EPA defines ecoregions as areas of relative homogeneity in ecological systems and their components. Drawing on the work of Robert Bailey and others, the U.S. EPA uses climate, geology, physiography, soils, and vegetation to designate ecoregions.

Bailey (1998, 7) contends that climate plays a primary role in defining ecoregions: “Climate, as a source of energy and water, acts as the primary control for ecosystems distribution. As climate changes, so do ecosystems….” As a result, weather patterns play an important role in ecosystem mapping as well as for planning and natural resource management. For example, watersheds can be used for flood-control management as well as water-quality planning. For both purposes, charting the amount of precipitation falling in a watershed, where it falls, and how it flows assists in the understanding of flooding patterns and water pollution levels.

Sociocultural Regions

Sociocultural regions represent a type of region that is elusive to delineate and to map. They may be defined as territories of interest to people that have one or more distinctive traits that provide the basis for their identities. Sociocultural regions may span several states, such as the Midwest, the Pacific Northwest, or New England; they may also be smaller areas that may span across a political boundary. For example, the general area of northern Indiana and southern Michigan is commonly referred to as “Michiana.”

Unlike many phenomena that constitute biophysical regions, people with widely varying social characteristics can occupy a sociocultural region. In addition, human movement in response to seasons means that different populations may occupy the same space at different times of the year. For example, an Idaho rancher will move livestock out of the high country in the autumn to lower elevations with warmer temperatures. In winter, the same Idaho mountains attract skiers from settlements located at lower elevations.

ECONOMIC REGIONS

Functionally, economic regions overlap sociocultural regions. Economic processes often dominate our view of social processes in regions. For example, daily trips to work, newspaper circulation areas, housing markets, and sports teams may define economic regions. Regions may be branded based on their economic health, such as the Rust Belt in industrial decline in the northeastern United States, and the robust Sun Belt in the South and the West.

Agricultural regions are another common delineation of this type; they are often a synthesis of all regional types. The basic resources of agriculture encompass the biophysical factors of soil, water, and plants; and the sociocultural factor of people, with climate providing a linkage, a measure of coincidence for the production of food and fiber. Frequently, labels from agriculture substitute as synonyms for more incorporative regional types: for example, Cotton Belt for the southeastern United States and Corn Belt for the Midwest, or, even more specific, the Napa Valley of California and the Kentucky Bluegrass region. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has defined new farm resource regions, which break away from following state boundaries to more accurately portray the geo- graphic distribution of U.S. farm production. The intent is to help analysts and policymakers better understand economic and resource issues affecting agriculture.

METROPOLITAN REGIONS

Throughout the United States, metropolitan areas have organized political bodies that address multiple planning issues, including transportation, economic development, housing, air quality, water quality, and open-space systems. These organizations encompass more than one political jurisdiction.

Metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) are responsible for planning, programming, and coordinating federal highway and transit investments. In addition to MPOs, other regional entities with planning responsibility include councils of government, planning commissions, and development districts.

There are more than 450 regional councils of governments in the United States. These are multijurisdictional public organizations created by local governments to respond to federal and state programs. A board of elected officials and other community leaders typically governs regional councils. Further information on regional entities is available through the National Association of Regional Councils and the Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations.

For example, the Portland, Oregon, Metro guides regional growth through the coordination of land-use and transportation plans. As an elected regional government entity, Metro provides such a platform for the Portland metropolitan region of 3 counties, 24 cities, and 1.3 million people. Metro’s capability to guide growth derives from Oregon’s planning law that requires comprehensive plans with housing and land-use goals as well as urban growth boundaries. Another example is the Metropolitan Council of the Twin Cities, which has coordinated control over transit and transportation, sewers, transit, land use, airports, and housing policy (Orfield, 1997). A regional planning council since the 1970s, Metro Council was strengthened through the Metropolitan Reorganization Act to address regional concerns regarding affordable housing, land-use planning, and economic disparity, among other issues.

CHALLENGES TO DEFINING REGIONS

A region forges a complex entity that involves many phenomena and processes. Information about these phenomena and processes must be ordered. This involves establishing cores and boundaries, hierarchical classifications, and interrelationships. On a map, regional boundary lines—be they water- sheds, jurisdictions, or newspaper circulation areas—can be carefully rendered. Such boundaries can tend to appear more real than the zones they symbolize and divert attention from actual connections and separations. Boundaries are most often determined for planning purposes through the political process. Goals can be established for planning in a variety of ways, and these goals result in irregular boundaries, a well-recognized problem of regional (and other levels of) planning. A significant difficulty in preparing, and especially in effecting, regional plans is that most “real” units rarely coincide with governmental jurisdictions. The boundaries of metropolitan areas enclose other municipalities and overlap with additional authorities. Watersheds seldom occur entirely within a single state or province, and many of them cross international borders. Although challenging jurisdictionally, watersheds are often advocated as an ideal unit for regional planning.

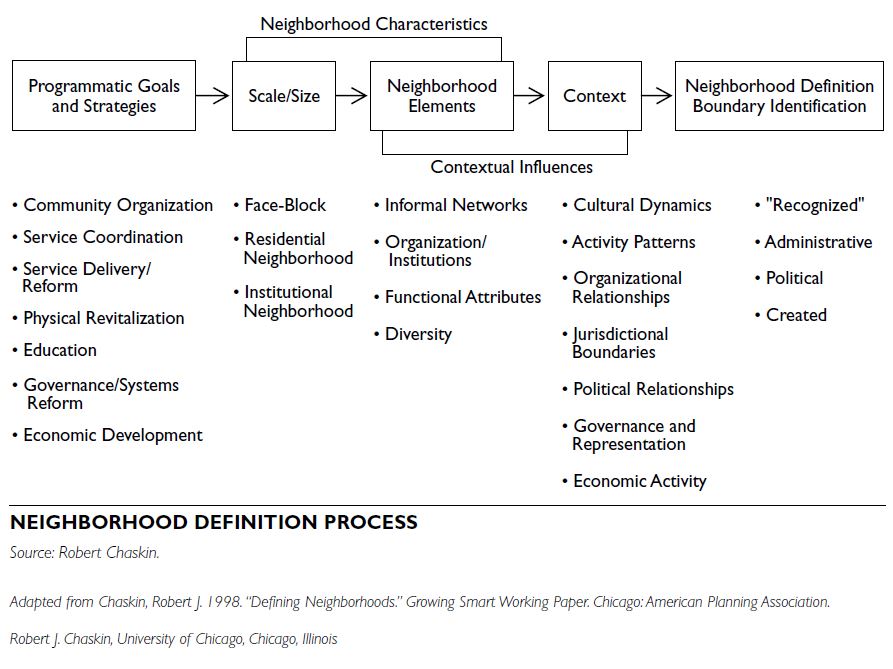

Neighborhoods have long been a focus within the planning field, and neighborhood-based planning is an area that continues to grow. Among other purposes, such an approach is increasingly seen as an essential part of a comprehensive planning process to inform citywide policy and to gain input, clarify priorities, and garner support for the neighborhood- level details of such plans (Martz 1995; Rohe and Gates 1985). Defining neighborhood for programmatic ends in any given case is problematic, however, because selecting and defining target neighborhoods is a highly political and negotiable process.

DEFINING NEIGHBORHOODS

There is no universal way of defining the neighborhood as a unit. When engaging in neighborhood collaborative planning, the process of neighborhood identification and definition should be considered as a heuristic process, guided by programmatic aims, a theoretical understanding of “neighborhood,” and descriptive information on the ecological, demo- graphic, social, institutional, economic, cultural, and political context in which the area exists.

There are three dimensions to this heuristic:

- Program goals and strategies

- Neighborhood characteristics

- Contextual influences

Their consideration should be an iterative process, each stage of which is informed by the preceding stage(s), and in the aggregate providing the basis for an informed choice of neighborhood boundaries and an operational definition of neighborhood for given programmatic ends.

Framing the consideration of these dimensions is a set of general propositions that inform the process of neighborhood definition in any programmatic context:

A range of criteria is available that might be used to define particular neighborhoods for given programmatic ends. The process of neighborhood definition proposed here involves attention to these criteria through an iterative series of deliberations, beginning with an articulation and clarification of programmatic goals. These goals reflect assumptions about what needs changing. Program strategies reflect hypotheses about how such change might be brought about.

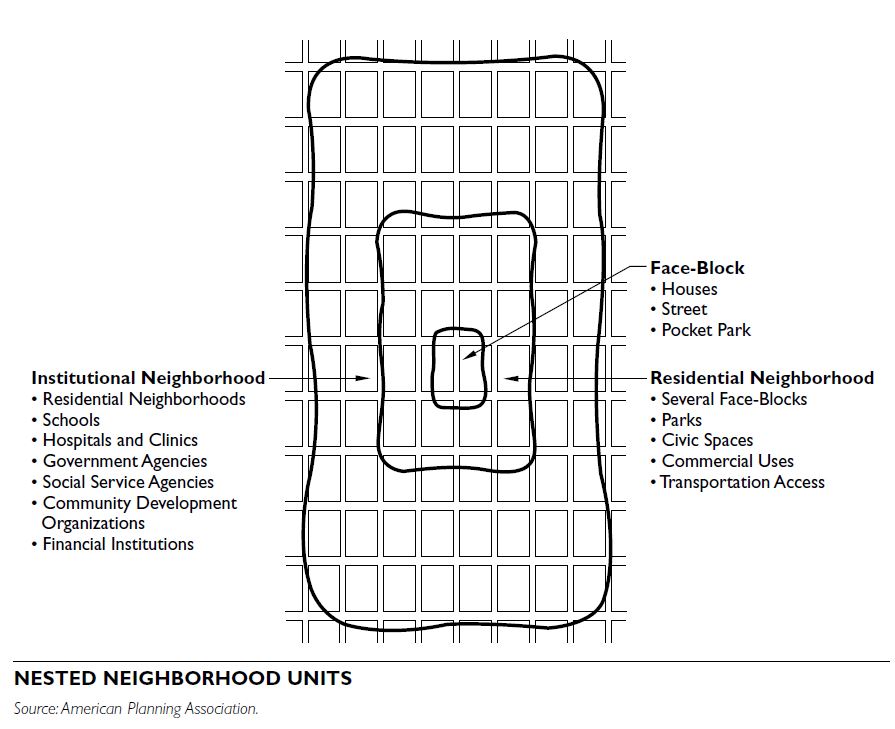

NEIGHBORHOOD SIZE

Consideration of neighborhood size should be related to the strategic intervention, operational focus, and desired impact of a given initiative. Three types of possible neighborhood constructions most useful for guiding neighborhood definition are the face- block, the residential neighborhood, and the institutional neighborhood. These units are nested constructions, each of which provides certain possibilities and constraints for fostering certain kinds of change.

Face-Block

The neighborhood as a face-block is defined as the two sides of one street between intersecting streets. As a planning unit, the face-block focuses on the interpersonal and provides a high level of opportunity for individual participation. Block-level planning will necessarily focus on a small-scale change, because individual blocks command limited resources and are too small in themselves to wield much influence in the broader community.

Residential Neighborhood

This construction focuses on neighborhoods as places to live. As a planning unit, the residential neighborhood provides an opportunity to engage residents in planning through different kinds of local governance mechanisms that can incorporate direct participation and potentially operate as a link to the larger local community. Planning at this level is likely to focus on local issues pertaining to quality of life, including housing, parks, commercial amenities, and transportation access. By itself, the residential neighborhood is less likely to be an appropriate unit of planning targeting broader systems change, seeking to foster institutional collaboration, or attempting to support economic development.

Institutional Neighborhood

The institutional neighborhood is a larger unit that has some official status as a subarea of the city. The institutional neighborhood provides the opportunity to focus on organizational and institutional collaboration and may require the construction of formal mechanisms for citizen participation if individual residents are to be directly represented.

NEIGHBORHOOD ELEMENTS AND CHARACTERISTICS

The consideration of scale of operation has implications for whether particular kinds of neighborhood elements are to be incorporated within the boundaries of a target neighborhood. It is clear that some such characteristics may be more important for the accomplishment of some programmatic goals than others.

Informal Networks of Association

While the existence of or potential for informal net- works is clearly central to initiatives seeking to develop or strengthen the social organization of a neighborhood, they are also of implied importance in any neighborhood-based endeavor. The informal social organization of a neighborhood, including neighbor relations, activity patterns, and informal service provision, differs across neighborhoods and for different populations (Lee, Campbell, and Miller 1991; Wellman and Wortley 1990) and may provide mechanisms for agency and social support overlooked in more formal approaches to neighborhood.

Formal Organizations

The availability of neighborhood organizational resources and their use also differs across contexts (Furstenberg 1993). The inclusion of formal organizations is especially important when initiative goals focus on systems change, service provision, or economic development. Because one assumption behind neighborhood-based work is that it provides the opportunity for greater access by and accountability to residents, neighborhood definition should take into account relationships among organizations and between organizations and residents.

Functional Attributes

Functional attributes include those elements necessary for day-to-day living, such as the existence of commercial activities, employment opportunities, recreational facilities, educational opportunities, and health and social services (Warren 1978). The existence of each of these elements represents a portion of the neighborhood’s capacity to sustain certain kinds of activities and promote certain kinds of change (Chaskin et al. 2001).

Population Diversity

The relative importance of population diversity or homogeneity depends greatly on an initiative’s particular goals. From an organizing perspective, homogeneity is likely to be beneficial, because it provides a clear basis for identity construction and mobilization of residents—particularly in smaller, residential neighborhoods. In larger neighborhoods and where fostering links to the larger community is desired, diversity may be valuable. This is in part a political issue, offering an opportunity to build coalitions across a broader range of constituencies. It may also be an ideological issue, in which promoting diversity is seen as a virtue in its own right.

NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT

Neighborhoods exist in specific contexts, and grounded information about these contexts is essential to any planning process. In addition to socioeconomic and demographic data, other tools such as community assessments, community inventories, and techniques for mapping neighborhood assets can provide valuable information on organizations, available facilities, and resident skills and priorities (Kretzman and McKnight 1993; Bruner et al. 1993). While much information is available through the U.S. Census and various administrative sources, a great deal of (often qualitative) data may not be readily available. The relational dynamics among these elements within the neighborhood, for example, and with actors beyond the neighborhood may be important for both the definition of neighborhood in given programmatic cases and for ongoing planning and implementation. Identifying and determining the most useful boundaries of particular target neighbor- hoods for programmatic purposes is much enhanced by the ability to map such relationships, and the ability to inform an interpretation of the impact of such relationships through a qualitative understanding of their dynamics.

BOUNDARY IDENTIFICATION

The criteria for boundary selection should reflect the goals and strategies of a given initiative, consider con- textual influences, and examine the sets of choices made regarding appropriate neighborhood scale and the relative importance of various neighborhood elements. The typology of possible neighborhood definitions implies certain guidelines regarding boundary identification: the face-block is bounded by the first streets that separate a resident’s home from the aggregation of homes beyond; the residential neighborhood implies some consensus regarding boundaries on the part of residents; and the boundaries of an institutional neighborhood have been in some way made official, codified and recognized by certain organizations and institutions.

“Recognized” Boundaries

Consistent with the assumptions behind the residential neighborhood, “recognized” boundaries imply the existence of some degree of neighborhood identity and provide the basis for fostering a sense of community. To the extent that the larger local community also recognizes such neighborhood definition, it may help residents and neighborhood groups to advocate their causes with government and other extra-local entities.

Administrative and Political Boundaries Administrative or political boundaries tend to define larger areas. Given a more systems-oriented or institutionally based approach, the use of such boundaries to define the target neighborhood may be appropriate. However, rarely do administrative and political boundaries coincide with each other, nor do they reflect the social organizational aspects of neighborhoods. The choice of a set of administrative boundaries to define neighborhood may be most useful for sector-bound, institutionally based interventions.

Created Boundaries

Institutional neighborhoods may be officially defined without functioning as an administrative unit. However, because such neighborhoods have no single administrative structure and are rarely recognized as political units, issues of management and long- term representation should be examined. The creation of a neighborhood governance structure that can coordinate constituent neighborhood priorities and activities, as well as represent the neighborhood to the larger community, may help to increase the long-term impact and sustainability of neighborhood- based work.

CONCLUSION

While these guidelines can help direct a process of neighborhood definition, they do not constitute a definitive blueprint for action. The act of defining a neighborhood is a product of both the social and spatial context of the area and subject to several factors, including the purpose for defining the neighborhood, the function that the neighborhood is expected to perform, and the presence of existing neighborhood organizations. Further, the delineation of boundaries is a negotiated process; it is a product of individual cognition, collective perceptions, and organized attempts to codify boundaries to serve political or instrumental aims. The attempt to define neighbor- hood boundaries for any given program or initiative is thus often a highly political process. These and other factors have to be considered during the plan-

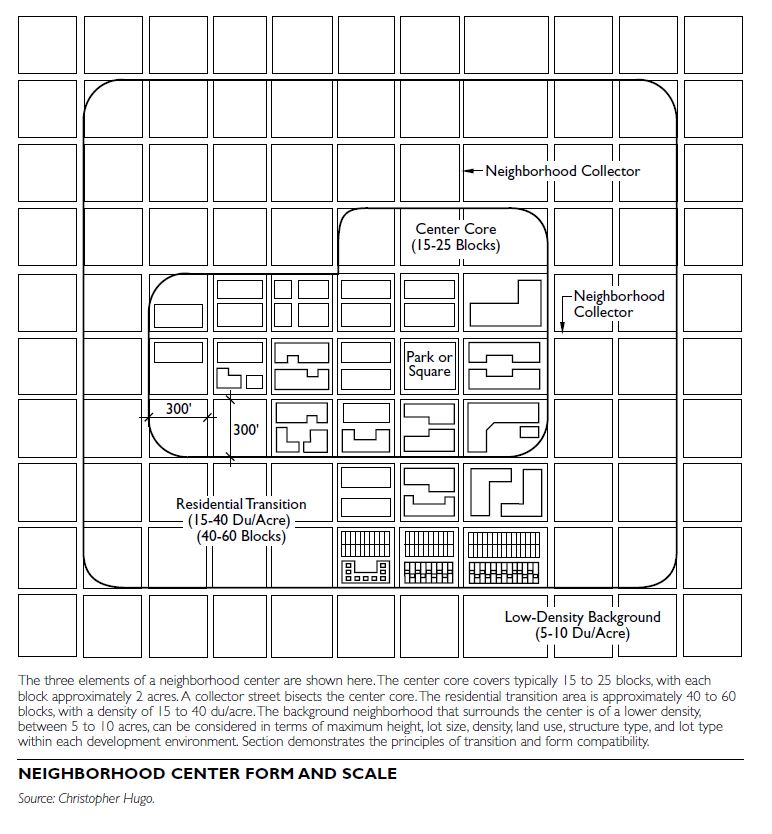

Neighborhood centers are the areas of more intensive urban uses within a neighborhood. They provide the most localized availability of goods and services needed daily by area residents. A center provides the social and operational focus of a neighborhood. Residential uses and neighborhood-oriented, mixed- use development are inherent to neighborhood centers. Centers can be retained, preserved, revived, or created. They can be planned in new communities, converted from suburban malls, or restored from distressed inner-city neighborhood business districts. Neighborhood centers play an important role in restoring neighborhoods as the building blocks of community.

COMMUNITY GOALS AND PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS

When planning for a neighborhood center, the community may identify several goals for the center:

These goals are then translated into planning considerations:

WALKABILITY AND NEIGHBORHOOD CENTERS

The viability of a neighborhood center depends on the degree of dependency that can be established between the uses in the center and the neighborhood population. This is a function of the number of people that are within a walkable distance of the center. This walkable population must be of sufficient size to provide a consistent source of demand for the center’s retail goods and services. Local market conditions, such as per capita disposable income and regional competition, will generate different popula- tion thresholds for this demand. However, the average population density that is within the walkable distance to the center must be several times the density of the neighborhood outside the center, called the “background” density. In traditional low- density neighborhoods, the background density is typically around 15 people per net acre (6 du/acre X 2.5 pp/du). For the center, an average density of 45 people per net acre (30 du/acre X 1.5 pp/du) should be the target, with a somewhat lower density near the edges and higher in the middle of the center.

PLANNING GUIDELINES

The following are planning guidelines that can serve as a basis upon which to start identifying potential sites for a neighborhood center. The criteria included below assume typical urban residential densities of 5 to 10 dwelling units/acre. Criteria should be modified to suit the particular conditions of a community.

Even at a relatively low net density of 6 units per acre, a typical 1-square-mile detached, single-family neighborhood has a resident population of around 7,000 people. A neighborhood center that accommodates 2,000 to 3,000 additional residents increases neighborhood demand for goods and services by approximately 25 to over 40 percent. The added convenience of proximity increases the rate of patronage of the center’s residents, raising the market capture of center businesses even more.

PROGRAM GUIDELINES

The program that directs the composition of a neighborhood center can be defined according to either conventional zoning or form-based zoning. Conventional zoning will define a finite list of accept- able and prohibited uses, and often has to rely on imperfect information about current needs and future markets. Form-based zoning focuses more on providing a defined set of compatibility and operational standards, and assumes that anything that “fits” the neighborhood setting is appropriate. While more flexible, this approach has to rely on potentially imperfect assessment of the impacts that proposed uses may have. In either case, a development frame- work should set some minimum expectations for center composition.

When looking at the overall composition of a neighborhood center, the following ratios can generally be applied to the division of land uses, expressed in gross aggregate site area:

- Between 40 and (preferably) 60 percent in higher- density residential use

- Between 20 and 30 percent in mixed-use retail and service uses, with residential above

- The remaining 10 to 40 percent (depending upon the composition of residential and commercial chosen) in public uses, such as a park, library, school or other public gathering spaces

A range of housing types in a variety of densities is essential to create transitions in use intensity and to respond to changes in markets and lifestyles. Neighborhood Center Features The specific amount and mix of commercial uses in the center depend upon local conditions and are determined by a subarea or neighborhood planning process involving community stakeholders. A sample list of commercial uses includes the following:

Other features that should be included in every neighborhood center include sheltered transit stops along a primary street; defined pedestrian routes connecting the greater neighborhood to the center; a focal point, such as a square or public facility, for example, a library; and imageability, which considers architectural compatibility, preserved history, consistent signing, controlled lighting, distinct street furniture, and other elements that add to the neighborhood’s identity as a distinct place.

FORM GUIDELINES

Neighborhood centers proposed for already-established neighborhoods need to be compatible with the current residents’ perception of “fit” and attractiveness. Form guidelines should be developed to create a center that is well integrated into the existing neighborhood fabric, respects existing residences, and advances the community’s planning considerations. The following are examples of such guidelines; again, the specific guidelines to be used should be developed based upon local conditions and community desires.

Blocks, Street Pattern, and Arterials

- Maintain a 300-foot maximum block length for circulation and increased business frontages. Longer blocks may be used for traffic control if fronting higher-volume arterials.

- Create or maintain a grid street pattern for circulation, ease of orientation, pedestrian safety, and street connectivity to all portions of the neighbor- hood.

- Reduce street curb-to-curb width to operational minimums. For example, a 2-lane street with parking on both sides can be designed to have a 32- to 36-foot maximum width.

- Avoid one-way arterials.

- Orient the core of the center on the intersection of neighborhood collector arterials; avoid spanning minor or principal arterials.

Center Core

Operational Guidelines

HISTORIC DISTRICTS

Historic districts are groupings of buildings and structures, noteworthy for their age, architectural integrity, or aesthetic unity. Downtowns, residential neighbor- hoods, and rural areas that have retained their historic character often receive official historic district designation. Historic district designation is an important tool for preservation-based revitalization, including downtown and neighborhood revival, with federal and state historic preservation tax credits often used to rehabilitate income-producing properties in these districts. There are two distinct types of historic districts: those that meet standards of the National Register of Historic Places, and local districts established by municipal ordinance, which are administered by a local review board. Although these two types of districts often possess identical geographic boundaries, there are significant differences in the nature of protection and financial incentives each can offer to a community.

NATIONAL REGISTER HISTORIC DISTRICTS

Established by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Register of Historic Places is the federal government’s official list of cultural resources worthy of preservation. This nationwide program coordinates and supports public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect historic properties and archeological sites. Listed properties include both districts and individual sites, consisting principally of architecturally significant neighborhoods and buildings. In 2004, there were 12,500 listed National Register Historic districts containing more than 1 mil- lion contributing buildings and structures.

All National Register properties have been documented and evaluated according to uniform standards established by the National Park Service (NPS), which administers this program. However, most nominations originate at the state level under the auspices of a state historic preservation officer (SHPO). Guidance for preparing such nominations is found in a number of how-to publications directly available from the National Park Service. The establishment of a National Register district involves submitting completed nomination forms and a narrative description of the proposed district to a statewide review panel, which must endorse it prior to its receipt by the National Park Service for final approval.

National Register Evaluation Criteria

The Code of Federal Regulations (36 CFR Part 60, National Register of Historic Places) contains evaluation criteria focusing on districts, sites, and buildings that possess integrity of location, design, setting, and workmanship. While some districts are associated with significant events in American history, or are directly associated with the lives of prominent individuals, it is more often the case that National Register districts embody residential neighborhoods or down- towns unified by distinctive architecture, in which most buildings were constructed more than 50 years ago. Broadly worded evaluation criteria have resulted in a wide diversity in the type and geographical extent of National Register districts found across the United States.

Districts, sites, buildings, and structures may meet criteria for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places if they:

- are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our nation’s history;

- are associated with the lives of persons significant in our nation’s past;

- embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction; or

- have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in prehistory or history.

Planning and Urban Design Implications

The National Register’s utility as a planning tool is derived from the National Historic Preservation Act, which requires federal agencies to consider the effects of their undertakings on historic properties, commonly known as a Section 106 Review. An undertaking is defined as “a project, activity, or program funded in whole or in part under the direct or indirect jurisdiction of a federal agency, including those carried out by or on behalf of a federal agency; those carried out with federal financial assistance; those requiring a federal permit, license, or approval; and those subject to state or local regulation administered pursuant to a delegation or approval by a federal agency.” At the local government level, the receipt of community development block grant (CDBG) funds or federal dollars to install a water main or replace a municipally owned bridge would trigger a Section 106 review.

Owners of private structures listed only in the National Register (and not otherwise part of a local historic district) are free to maintain or dispose of their property as they deem appropriate, provided that their actions require no federal license, permit, or funding—there is no obligation to restore or even maintain a federally listed historic property. But

because mapped boundaries of a National Register district are often identical to those of a local historic district, governing rules for the latter can provide a greater degree of protection than that offered under federal law. At times, property owner opposition can foil the establishment of a local historic district and the creation of its associated review board, as even the most ardent preservation advocates cannot deny that this will add an additional layer to a development over- sight process that may also require approvals from a planning board or zoning board. However, the guidance and rules these other boards must follow seldom focus on architectural or aesthetic features of a structure, or consider the extent to which its alteration or demolition would impact a neighborhood’s historic character. In the absence of a local historic district architectural review process, the composition of established neighborhoods and business districts risks erosion, and visual character of a community may be irreparably altered.

Financial Incentives for Historic Preservation

Jointly managed by the National Park Service and the Internal Revenue Service, in partnership with State Historic Preservation Offices, the federal historic preservation tax incentives program rewards private sector rehabilitation of historic buildings. The certification process for this program is outlined in the Code of Federal Regulations at 36 CFR Part 67. Properties individually listed in the National Register or those located in a National Register district and certified by a SHPO as being of historic significance are eligible.

Since 1976, these federal tax credits have stimulated more than $18 billion in private investment, and have contributed to the rehabilitation of more than 27,000 historic properties containing more than 30,000 units of low- and moderate-income housing. However, eligibility requirements for federal historic preservation tax credits provide that such properties must be income-producing and be rehabilitated according to architectural design standards set by the Secretary of the Interior. Properties receiving federal tax credits may be used for offices, for commercial,industrial, or agricultural enterprises, or for rental housing, but they may not serve exclusively as a private residence.

A number of additional financial incentives are available to assist communities undertaking historic surveys, or help out property owners willing to restore their buildings in a historically appropriate fashion. A key thread running through virtually all these programs is the need to adhere to the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation and the requirement that properties be individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places or located within a National Register district.

LOCAL HISTORIC DISTRICTS

Charleston, South Carolina, established America’s first local historic district in 1931. Today, it is one of the country’s largest, encompassing 3 square miles and nearly 4,200 contributing structures. Fueled partly by federal involvement in historic preservation beginning in the 1960s, every state has enacted legislation authorizing local preservation ordinances, enabling creation of historic districts and local boards or com- missions charged with the review and approval of development activities taking place within these districts. Common to virtually all local historic districts are administrative rules intended to preserve a structure’s exterior appearance and setting relative to the historical architecture and settlement pattern characteristics of the neighborhood. These rules are typically expressed in a historic preservation ordinance and administered by a locally created review board.

Certified Local Government (CLG) programs allow municipalities to participate more directly in state and federal historic preservation programs. To become a CLG, a local government must enact a local preservation ordinance that meets federal standards and establishes three basic items:

Benefits of becoming a CLG include special grants, professional legal and technical assistance, training, and membership in the national historic preservation network.

HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEYS

Conducting a historic resources survey is the first step in both federal and local historic district designation. This survey identifies and evaluates all contributing structures within a proposed historic district. Extensive documentation is required, including a field inventory to visually evaluate buildings and structures, and research in libraries, newspaper archives, and municipal records. Key elements of a completed historic resources survey are described here.

Structure Inventory Forms

Structure inventory forms describe a building’s architectural style, level of detailing and craftsmanship, and integrity or alterations to its original character.

Photographs

Photographs of a building’s exterior elevations, generally of archival print quality, are included.

Maps

Maps depict the exterior boundary of the historic district and locations of all contributing structures, cross-referenced to each structure inventory form. The map should be capable of yielding a written description of the historic district boundary. Fire insurance maps from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries can help establish relative dates of neighborhood development.

Narrative Report

The narrative report describes the methods used to determine the boundary and conduct the survey, the district’s historical development, the relationship of contributing structures to one another, and buildings that are noteworthy for important personages or architectural significance. This report should also list primary and secondary written materials encountered during the research. It is appropriate to identify potential threats to a neighborhood, such as deteriorating buildings neglected by their owners, architecturally intrusive noncontributing structures, and income-producing properties that may be eligible for federal tax incentives for rehabilitation.

Request for Qualifications

These survey elements can be embodied into a Request for Qualifications, used to solicit proposals from historians, architects, or architectural historians whose education and training meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Minimum Professional Qualifications Standards (36 CFR Part 61, Appendix A). A SHPO should be able to provide a prequalified list of acceptable consultants meeting these standards, which are requisite for preparing nominations to the National Register of Historic Places.

LOCAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION ORDINANCE

An ordinance is necessary to identify procedures for creating local historic districts and administering the review of building renovations or alterations to properties located within the district. It should reference the legislative intent of the state enabling act, which grants municipal authority to establish historic districts. The ordinance should require a survey to identify and evaluate all contributing structures, and the preparation of a map depicting district boundaries. It typically establishes a historic district commission or architectural review board that is charged with the review of development proposals within historic districts.

Some states require a vote of approval by a majority, or even two-thirds, of the residents of a proposed local historic district. In other states, a city or town council is empowered to establish a local historic district after conducting a public hearing.

Historic District Commission/Architectural Review Board

A local historic district commission, which may be known as a heritage preservation commission or an architectural review board, depending on the nature of the ordinance, administers a process sometimes referred to as “historic district zoning.” These boards are distinct and separate from planning or zoning commissions. They have their own rules of procedure and issue their own approvals, known as certificates of appropriateness, when approving construction plans. The historic district commission’s actions do restrict what a person can do with their property; however, there is a significant body of case law that supports the right of a community to regulate a building’s visual and historic character.

The review board’s jurisdiction typically includes exterior renovations, building demolition, and new construction. The board may also be responsible for approving façade improvements and signage in order to protect and enhance the visual character and encourage economic development in commercial neighborhoods. Some communities allow “minor work” such as repair or replacement of exterior materials with identical or similar materials to be reviewed by staff, with an appeal to the full board if necessary. When creating a historic district commission, the local governing body should appoint members who have a background in history or architecture. These qualifications are necessary to meet National Park Service criteria for a certified local government (CLG).

Certificate of Appropriateness

The architectural review process begins when a property owner applies for a building permit for repairs or alternations to structures located within a local historic district. The historic district commission or architectural review board grants a certificate of appropriateness prior to the issuance of the building permit or certificate of occupancy. Each commission develops its own written procedures and standards guiding modifications to historic buildings, but the most commonly used measure is known as the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation (36 CFR Part 67, Historic Preservation Certifications), which is also used to administer the federal historic preservation tax credit program.

Appeals

Local preservation ordinances should also contain a provision for property owners to appeal the decision of a historic district commission, with such appeal directed toward an existing entity such as a zoning board of review. When considering appeals, the zon- ing board of review should not substitute its own judgment for that of the historic district commission, but rather consider the issue upon the findings and record of that commission

CHALLENGES TO HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION

Planners should be aware of arguments used by opponents to historic district designation, who may raise concerns about added construction costs or excessive regulation.

One ongoing debate is that historic district commissions “fossilize” neighborhoods by imposing very narrow or personal definitions of appropriateness that discourage architectural creativity and diversity. Others argue that compliance with architectural design codes restrict the ability of businesses—particularly national franchises—to adjust to market conditions, or are beyond a homeowner’s financial capacity to carry out needed exterior renovations. Indeed, blight becomes an issue when property owners fear or resent an additional layer of bureaucracy, or cannot afford historically appropriate building improvements.

To prevent individual board members from becoming arbiters of “good taste,” historic district commissions from the outset must have clearly written specifications to determine what constitutes appropriate construction or renovation, and what will add or detract from a historic streetscape. This is why local boards are encouraged to rely on the nationally accepted Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, possibly supplementing these with more detailed guidelines that are specific to a particular district. Proper documentation will elevate the review process above personal preference or bias, and thus provide a consistency of decision making.

It is recommended that historic district commissions prepare an informational pamphlet that addresses the concerns of property owners, builders, and architects. Pamphlets should summarize the historic preservation ordinance’s guiding principles and procedures, list which actions are exempt from design review, and provide graphic illustrations of the types of improvements that would be granted a certificate of appropriateness.

A final challenge is “demolition by neglect,” which is defined as the destruction of a building through abandonment or lack of maintenance. This problem is attributable to impoverished owners, difficulties arising from unsettled estates, or uncaring absentee landlords. It is important, therefore, that property owners be made aware of financial incentives that can assist in rehabilitation.

Current interest in the water’s edge and the flourishing of public spaces on waterfronts across the United States is the result of a process going back for decades. Once places of trade, military, or industrial advantage, or even places of neglect, waterfronts are increasingly seen as economic and social assets to their communities.

STANDARDS AND REGULATIONS

When contemplating new waterfront projects, take into account the specific standards enforced by federal and state regulatory systems. The following agencies have a role in the regulation of our coastal ecosystems.

Federal Agencies (for Navigable Waterways and Connected Wetlands) - U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) - U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration (NOAA) - The Department of Homeland Security (especially the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the U.S. Coast Guard) - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

State and Local Authorities

MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

To understand a waterfront, study its evolution. Consider the shoreline’s various stages of development. Create a series of diagrams analyzing the historic and current conditions of the water edge, which will be critical in designing its future uses. In addition, understanding the sectional analysis of a coastline is important when planning a new use on the water and its connections to the built fabric of the city.

Natural Edge

A natural edge diagram describes the undisturbed conditions of the shoreline’s ecosystem and its often rich variety of species. Such natural conditions might be used as a benchmark for waterfront restoration.

Productive Edge

A diagram of the waterfront’s historic productive uses can be helpful when planning new uses on the water. Maintaining productive waterfront uses is often a priority. Elsewhere, historic artifacts might be incorporated in a new design as cultural and perhaps functional features, such as old gantries, working piers, and cranes. Historic interpretation can be important for the new design by creating a strong identity of a place rooted in the region’s past.

ANALYSIS OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECOLOGICAL WATERFRONT CONDITIONS

Pollution and deterioration of the coastal environment often requires major investment in its restoration, considerably increasing a project’s total cost. Pollution mitigation, remediation, stormwater management, stream and wetland restoration, and habitat protection are some of the basic aspects of waterfront restoration and development.

Environmental education is a key component in successful waterfront revitalization. Include design elements and signage that provide information about the historic uses of the waterfront area and its current environmental status. Consider alliances that involve local citizens and institutions in long-term restoration efforts. Inform the local community about the health hazards of activities along the new waterfront, such as fishing and swimming, if there is potential for danger.

Ecology of the Water Edge

Investigate ecological conditions at the shoreline to determine the type of cleanup and the subsequent appropriate ecological system when designing the waterfront. Often, this process can inspire the designer to incorporate ecological elements, both aquatic and terrestrial, into the new design, turning them into opportunities to educate and inform the public about the natural history of the shoreline.

Transportation and Connections Abandoned or active rail lines, freeway structures, neglected culverts, chain-link fences, walls, or even private gates can be obstructions to accessing the waterfront. Take into account their presence and potential for relocation when redesigning new water- front destinations.

Land Use

Many land uses can be found on the waterfront, depending on its economic and social function. Land uses can include industrial production, commercial development, transportation nodes, recreational uses, public infrastructure, institutional and educational structures, and new residential areas. Successful waterfront development will include several coexisting uses, providing urban vitality and activity at the water’s edge.

Environmental Factors

Given the heavy industrial uses that occurred on the shorelines in the past, cleanup processes and pro- grams play a fundamental role and are a key step in the redevelopment process of sites along the water- fronts. Soil analysis is a basic step in the challenging process of cleanup and restoration of a waterfront area. Cleanup costs can be substantial and can add to the total cost of a waterfront redevelopment project. Because of contamination in the ground, in buildings and other structures, and possibly in groundwater or adjacent surface water, state and federal environmental agencies and financial institutions often require considerable remediation or cleanup before redevelopment can occur, or as part of the redevelopment process. Of particular concern are any anticipated changes to a structure’s configuration. A brownfield, as defined by U.S. EPA, is a polluted property that in order to be redeveloped needs to undergo such cleanup process. Also, many jurisdictions prohibit additional fill or require mitigation measures to replace open water.

WATERFRONT DESIGN PROCESS

Because of the often controversial and political nature of waterfront projects, their development is a complex process involving many different state and federal authorities as well as grassroots organizations and community stakeholders.

Community Involvement

Involve the community from the beginning in water- front redevelopment projects. Educating and informing the community about the challenges ahead will create a strong foundation on which to draft a long-term vision for a new, inclusive waterfront. Environmental monitoring and education are effective tools to build a large community constituency, together with effective visioning tools such as community workshops and charrettes.

Remediation Plan

A remediation plan is necessary when high toxicity levels are found on-site. The intensity and thoroughness of the cleanup process differs with the specific uses planned for the site: a residential area, for example, requires a much higher level of remediation than an area for a parking structure.

Conceptual Framework Design

When designing a waterfront, issues of scale play a major role. A framework plan often builds on previous studies and has the overall planning of the area as a main goal. A comprehensive framework plan allows flexibility and leaves room for future land-use decisions regarding the waterfront. This type of plan ensures a cohesive allocation of investments, connects the new sites to the rest of the urban or rural developments, and supports appropriate uses on the water.

Detailed Design

A detailed plan finds its place within a strong frame- work and usually focuses on the appropriate specific program for an area. A detailed plan for a waterfront calls for new and reinterpreted uses and creates new places and destinations through the implementation of solid design guidelines.

WATERFRONT TYPES

Different waterfronts encourage different types of activities. River waterfronts promote activities enhancing connections across the two riverbanks: physical and visual connections are equally important in this kind of waterfront. Waterfronts by the ocean or the bay connect the urban fabric to activity nodes along the water and promote the use of piers for recreational activities. Finally, a body of water such as a lake or a reservoir promotes activities around the edge, invites points of activity along the shore, and is a great setting for water-related sports.

WATERFRONT DESIGN COMPONENTS

Waterfront projects can have different scales, from a plaza to a greenway, and different character, from container port to wetland. Waterfront components can be a series of open-space elements, a system of connections to the inner core of the city, a new development on the water, or a strategy for sustainability.

Design Strategies

Consider the following overall strategies for the design of a successful waterfront area.

Continuity: A continuous waterfront system for walking, jogging, biking, and rollerblading.

Sequence: A sequence of recurring open spaces at significant points along the water. Such places might have a special view or might be directly aligned with major city streets.

Variety: Multiple uses along the water create successful synergies and accommodate different users.

Connection: Visually and physically connect spaces along the waterfront and from the new waterfront to the bay (with views and piers) and to the city (through access points and pedestrian circulation links).

Design Elements

Open Space

Plazas: Waterfront plazas are often part of larger waterfront developments, such as commercial and recreational buildings along the water. They are often hard-surfaced areas with seating, shaded areas, and prime views of the water. In larger developments, plazas can be designed to allow for large recreational gathering structures such as amphitheaters or stage areas where local civic events can be held. They also offer great opportunity for displaying the historic memory of the waterfront through interpretive features or art installations.

Parks: Along the water, parks can be hard- paved areas or more natural soft areas. A new park can also be connected to a local ecosystem, such as a wetland, and to larger natural areas, such as greenways along the shoreline.

Piers: Piers can be interesting components in the redesign of waterfronts. They can reinterpret history, provide views, and promote recreation such as fishing. Incorporate safety elements such as lighting and railings, as well as sitting areas with benches to rest and enjoy the view. Focal elements such as art installations or small commercial buildings can be included at the end of a pier to make walking and strolling along its length a more exciting activity.

Connections

Paths: Biking and jogging are among the more iconic uses of a recreational waterfront. Water views and linear, often unobstructed, connections along the water make these activities especially pleasant. Design paths to accommodate these activities. Use smooth paving materials in areas for bikes, and ensure that path widths accommodate bikers and walkers alike, possibly with separate rights-of-way.

Promenades: A promenade can connect spaces along the water or be a destination in itself, offering recreational opportunities for strollers, joggers, bikers, and in-line skaters. Depending on the specific character of the waterfront, promenades can be constructed and sophisticated urban places or natural and understated linear connections. Design elements such as paving materials or light fixtures can vary according to such character. Accommodate biking and jogging activities with materials that can withstand the effects of the moist microclimate.

Water connections for tourists: Tourism can be an economic engine driving the waterfront redevelopment process. Water taxis and ferries can be tourist attractions, as well as interpretive tools of an area’s productive past.

Development

Water connections as mode of transportation: When waterfronts are more developed and can support a high number of residential buildings, water connections can become an effective mode of transportation, making the link between residence and work place an easy and interesting transit alternative.

Working waterfronts: In the past, waterfronts were the exclusive realm of harbors, fishing fleets, shipbuilding, warehouses, and manufacturing plants. Changing technology made some of these uses obsolete, and rising land prices connected to the rediscovery of the water edge have endangered many local maritime enterprises. These enterprises can add to the local economy and to the city’s character. Consider retaining and promoting existing maritime uses when possible, and integrate their needs with the overall plan of the new waterfront.

For large working ports, container handling, shoreline configuration, updated equipment, regional distribution networks, and environmental impacts are key planning issues. Planning efforts at many ports seek to designate safe and inviting locations for the public to view port activities.

Infill and adaptive use: Infill development can be a catalyst for change in forgotten areas of a waterfront. Adaptive use of historic buildings can be a powerful redevelopment strategy to create new destinations and to reinterpret the waterfront’s past in new ways. Successful renovations can generate dynamic synergies that can boost local economies and provide a sense of place.

Recreation and tourist destinations: The number of tourists it attracts is often the measure of a waterfront’s success. Promote tourism in the early phases of waterfront redevelopment to encourage investment. Educational, recreational, and interpretive features and activities are often found in the public areas of a waterfront, where visitors exploring the character of the region can readily appreciate a new identity anchored in the past.

New mixed-use development: After the initial success of a waterfront redevelopment, larger developments often follow. All uses benefit from the prime location and the recreational opportunities a new waterfront offers. Some jurisdictions invite residential uses along the water, to bring density and vitality to the area. Be sensitive when locating residential uses at the edge, to ensure public access is maintained.

Art: Public areas along waterfronts offer great opportunities for education and art appreciation.

In particular, the rich social and cultural heritage of these sites encourages artists and a municipality to collaborate in often striking public art projects that foster a sense of place. Allow flexibility in waterfront plans to ensure that art interventions and programs can be incorporated.

Sustainability

Ecological preservation: Every waterfront is part of a watershed. Consider sensitive habitats and floodplains during the design process.

Ecological design: Natural conditions of water- bodies and the edge conditions are increasingly seen as opportunities to inspire design and suggest uses along the water. Many new developments incorporate ecological design principles as powerful elements of the design concept. Ideas such as wetland restoration, native vegetation preservation, and stormwater management have created a new design vocabulary in waterfront planning.

Industrial parks are areas within a community designated for activities associated with industrial development, which can include materials processing, materials assembly, product manufacturing, and storage of finished products. Uses can include manufacturing facilities, warehouse distribution centers, and truck terminals.

Industrial parks can be stand-alone developments within a community, or they can be adjacent to or part of a larger regional industrial district spanning a number of contiguous jurisdictions. Industrial parks rely on the availability of large tracts of land, efficient transportation systems, and sufficient infrastructure for their success and for their ability to integrate into the larger community.

SITING PARAMETERS

Transportation

Industrial parks should be located in close proximity to major transportation systems, including regional and interstate highway systems, with an efficient system of local roadways between the industrial park and the highway system. Access to other types of transportation systems, such as rail, port, and air- freight, should be available, if they are characteristic of the region and in demand by the industry.

Utilities and Infrastructure

Industrial parks require dependable utility systems. Sufficient supplies of water for domestic fire protection and for use in industrial processes should be available, and sanitary sewer systems need sufficient capacity to support waste generated in the park. Adequate sup- plies of natural gas and electricity also are necessary.

Consideration should be given to developing regional stormwater management facilities to support the industrial park. Best management practices for stormwater quality and quantity are ideally developed on a district or regionwide basis, based on the watershed of the area. If this approach is not possible, on-site stormwater management facilities need to be provided. Open stormwater management facilities should be allowed within perimeter buffer areas and planted areas, to preserve other land areas for industrial development.

Industrial park developers must also take into account telecommunications utility infrastructure.

Land Area

The land area needed for an industrial park can range from 20 acres to hundreds of acres. An area between 50 and 100 acres in size allows for flexibility for parcels, planting, and internal transportation and parking systems. Large, rectangular tracts of land that are available for development at competitive prices in the region should be considered as sites. Land should have minimal impediments to development, to make it competitive in the marketplace. Conditions such as steep topography, exposed bedrock, wetlands, sensitive environmental areas, and irregularly shaped parcels can contribute to site development costs and inefficient use of the land.

Labor Force

Development of the industrial park will be directly related to the ability to attract labor from proximate areas to the park to serve the industry within the facility. The available labor force is directly related to the type of industry that can be attracted and the likely success of the park. Among the labor force considerations to assess are the following:

SITE DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

Organizational Systems

Industrial parks tend to be organized according to a grid system, to optimize flexibility in parcel shape and size. Internal street patterns also follow a grid, to accommodate heavy truck traffic. Newer industrial parks, which often include office space and require less excessive truck use, may use more curvilinear road systems that follow the natural contours of the land. Parcel sizes often vary, to capture changing market conditions. Most parcels are between 200 and 300 feet deep and allow for land to be resubdivided to create larger lots, if desired.

Circulation and Parking

Traffic, road, and parking standards depend on the uses allowed in the industrial park. Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) standards should be reviewed when developing the circulation and parking system for the area. These standards include road width and bearing capacity, truck loading and turning requirements, traffic generation guidelines, and parking requirements based on type of use. Major access points should not conflict with pedestrian movement or adjacent residential areas, and local traffic flow should not be disrupted as a result of truck movement.

Buffers and Open Space

Most industrial parks require planted buffers to separate them from residential uses. They also require sites to be planted and to retain tree cover. Modern industrial parks are often lower in density than older industrial areas; some require between 70 and 80 per- cent open space. Height and bulk standards, floor area ratios, and other density standards for structures should be compatible with competing industrial areas throughout the region, yet provide for land to be set aside for buffer zones, greenbelts, and protection of environmentally sensitive areas.

Structural Elements

While utilitarian industrial parks with inexpensive structures and minimum site improvements are often required for competitive reasons, enhanced design adds value to the industrial park, the community, the owners, and the employees. Among the elements of enhanced industrial park design are underground utilities, architecturally harmonious structures, planted areas, and road systems that allow for safe and efficient movement.

POTENTIAL IMPACTS

The compatibility of industrial uses with adjacent uses will depend highly on the type of industry that locates in the area. When considering an industrial park, the following are among the types of typical impacts from industrial uses:

Performance Standards

Industrial parks are increasingly governed by performance standards. In addition to the typical setbacks, buffers, and landscape planting requirements, these standards govern light and glare, noise, vibration, air pollution, odor, heat and humidity, electric interference, radiation, outdoor storage and waste disposal, traffic, fire and explosive hazards, and toxic and hazardous materials. Consult local regulations or published materials on industrial performance stan- dards to develop specific standards.

Park Covenants

In addition to zoning regulations, covenants can also be used to guide industrial park development. Such covenants can describe the type and character of industry allowed within the industrial park, general guidelines for building construction, environmental considerations, buffer zones, and overall general aesthetics. These assure potential users that their investment will be protected by similar development within the industrial park. Covenants can also be written so that existing users within the park have input into the approval of future users locating within the park. Like zoning regulations, park covenants should be clear and result in a positive conclusion when all conditions are complied with.

EMERGING TRENDS

Mixed Uses

Industrial parks of the past were typically confined to industrial-related uses; today, related uses such as manufacturing support facilities, office and office support, and research-related uses should be allowed in them. There are even circumstances where hotels and small retail activities can be sited in the industrial park. If they are desired, these uses should be placed on the periphery of the industrial park or in places that enable traffic to easily flow without intermingling with the core activities of the industrial park. Office uses, showrooms, and other ancillary or support functions such as conference and hotel facilities may be placed in the more visible areas of the park.

Eco-Industrial Parks

Eco-industrial parks are industrial parks in which ten- ants seek to minimize or eliminate waste generation, energy use, and other environmental impacts through symbiotic arrangements with other facilities in the park. Because of the interrelationships among the ten- ants, eco-industrial parks often require a more sophisticated management and support system than traditional industrial parks. Several eco-industrial parks are in operation in the United States, including Cape Charles, Virginia, and Londonderry, New Hampshire. Because of the reduced impacts of these facilities, they may be more compatible with nonindustrial uses than conventional industrial parks.

Eco-industrial parks can be described as generally having the following characteristics:

An office park is designed specifically to serve the office space needs of a wide variety of businesses. Office parks often include both multitenant office buildings owned by an investor, such as the developer, and properties built to suit the particular needs of a company. Office parks have evolved as master- planned, mixed-use developments incorporating a variety of ancillary uses such as residential, retail, entertainment, and recreational components. Developers of office parks often consider including neighborhood-type elements, such as retail establishments, entertainment and recreational options, green spaces, and, in some instances, residential development, along with other commercial uses such as light industrial buildings and medical office buildings. The overall goal is to create a vibrant, self-contained business community that is more than just a place in which to work.

TYPES OF OFFICE PARKS

Two of the most common types of developments today are campus-style office parks and urban-style office parks.

Campus Style

The campus-style park, typically a large, relatively self-contained development that could cover several hundred acres, is the more traditional type. To make the parks attractive to office space users, developers often add retail uses such as convenience stores, restaurants, and dry cleaners. Residential development, including for-sale and rental housing, is increasingly integrated into campus-style office parks. These types of office parks are more likely to be constructed in communities where there is an abundant supply of undeveloped land.

Urban Style

An urban-style office park is typically located within a more developed area of a community, where developable land is at a premium. Because of high land costs, these types of office parks are more likely to require higher-density development, including high-rise office buildings, to make them economically feasible. Increasingly, urban-style office parks are being built based on traditional neighborhood development (TND) or new urbanist principles, creating places where people can “live, work, and play” in the same setting. For-sale and rental residential housing, along with entertainment, retail, restaurants, coffee shops, hotels, and outdoor recreational amenities is among the variety of mixed-use components developers use to make urban-style office parks attractive places in which to do business.

SITE LOCATION PARAMETERS Location is the primary component of a successful office park development. Highly competitive market conditions and high land costs make it imperative to choose a site that contains all the necessary features and has a need for such development.

Site Size

Office parks are built over many acres—project sizes can range from 20 acres or more for an urban-style office park to several hundred acres for a campus-style office park. An adequate amount of space is needed to accommodate all the uses for which an office park is intended and to create a unique environment that appeals to the end users. Office parks often serve as anchors for a new town center development that encompasses a substantial quantity of land.

Access and Transportation

Convenient highway access is typically a critical factor in locating a campus-style office park. The local street system must be able to handle the increased flow of vehicle traffic that an office park will generate so that the customer can quickly get to a destination. Access to local and regional transit systems is also an increasingly important aspect of office park development. Because of the concentrated number of people in a park, office parks can provide a community with an opportunity to enhance its overall transit system, through the development or expansion of a regional transit hub adjacent to the development.

Visibility

Visibility is one of the key factors that business space users rely on when choosing a site location for their company. An office park needs to stand out both physically and visually as a readily identifiable feature of the local business landscape and a recognizable component of a community. Some of the ways to accomplish this could be a recognizable building or tenant name, monument signage, or a unique landscape or art form.

Demographics and Trends

Part of the location selection process is researching the community to determine the likelihood of attracting enough business users to make the park successful. This includes understanding the demo- graphic makeup and trends that exist in the local and regional business community. Rather than waiting for the market to respond when a new project is launched, office park developers often seek to create value and generate substantial revenues from the project in as short a period as possible, to recoup initial investments and cover ongoing land, investment, and development costs. For this reason, developers favor providing a mixed-use development, which allows the developer more quickly to absorb the land and put it into productive use.

SITE DESIGN

Specific site design issues will depend upon the number and type of tenants that will occupy the park. Local regulations also provide minimum standards required for each design issue. A planned unit development can give a developer an opportunity to create a unique environment with more design flexibility relative to standard regulations. Below are some of the commonly addressed site design issues.

Circulation

Employees, vendors, and customers must be able to travel to and from their destinations within the office park in a convenient and timely manner. The side- walk, path, and street network should be designed to facilitate efficient movement patterns.

Parking

Parking requirements will vary depending upon the number and size of buildings and the types of uses included in the office park. Facilities with access to transit, organized carpooling, and other options that may reduce vehicle trips require fewer parking spaces than those where such options are not avail- able. When creating a mixed-use office park, shared parking opportunities may be available. An example is a movie theater located next to an office building: these two facilities could share a parking area because the hours of operation of each are different and rarely conflict. Local regulations should be consulted to determine actual parking requirements.

Building Height and Massing

Office space is changing from its past configuration. The average ratio of office space per employee is shrinking from 250 feet to 150 feet per employee, and companies are increasingly locating as many employees on the same floor or on contiguous floors as possible, to minimize disruption in business operations. Floorplates for office buildings, which previously were between 22,000 to 26,000 square feet, are now much larger, up to 45,000 square feet. Therefore, there are more employees, requiring more parking needs.

Utility Systems

Office parks require utility systems that support all of the necessary operations within the buildings, and adhere to building and fire codes. Utility factors deemed critical by business space users today include underground utility connections, redundant electrical power sources, state-of-the-art fiber-optic connections, and access to satellite-based communications.

Urban office parks often have double and triple power redundancy and access to multiple data “pipe” supplies. Campus-style office parks are more likely to rely on a generator for power backup.

Electricity

Electrical requirements should be determined based on the use of the building. However, most large facilities now require that standby generators be provided on-site to supplement public supplies, should an out- age occur.

Natural Gas

A source of natural gas is generally required for heat- ing and air conditioning, as is a source of emergency power to operate the building during power outages or as a backup source of power to computer systems.

Sanitary Sewer

Office parks require either the service of municipal sewer systems, in order to serve the buildings, or sufficient land area for the on-site disposal of wastewater. Local and state codes should be referenced prior to siting an office park to determine the feasibility of on- site wastewater treatment and disposal, based on the quantity of wastewater generated.

Water Supply

Office parks will need access to a water supply, typically provided by a municipal water authority.

Stormwater Management

Runoff from paved areas, especially parking lots, has the potential to create stormwater management issues. Sufficient land area must be available to provide on-site stormwater collection, and management facilities must meet Clean Water Act best management practices and local regulations.

Aesthetics

Among the elements used to address the aesthetic elements of office parks are standards for building

materials and uses, overall architectural design, vegetation, signage, and lighting. These elements help provide a specific identity for the office park, which is important to the developer’s marketing efforts and to park tenants. Most business parks have protective covenants for this purpose.

Open Space